Self Organizing Systems

A reflection on my career path, a look at Frederic Laloux’s book “Reinventing Organizations”, and resources from Margaret Wheatley

My introduction to the concept of self-organizing systems was through my business partner, Gustavo—in his past engineering roles, he worked with high growth tech companies to build out teams of engineers. We’re talking hundreds and hundreds of engineers. What do you do with so many builders of code?

Gustavo explained his techniques of setting the tone for the engineering department, namely that of autonomy. Engineers were hired because they knew how to code, to Gustavo this meant there was no need to “manage” them in the traditional, hierarchical sense. Instead, for Gustavo it was important to create a structure within which the engineers could code, build and experiment. The key ingredients are having shared goals and vision, and most importantly, trust. Trust in your team and in your own abilities. This, in a nutshell, is what makes a self-organizing system.

Over time as Gustavo shared his perspectives on work practices, I reflected on past professional experiences—has self-organizing been part of my path? If so, how? If not, what was I missing? I also fell back on my research skills, looking into self-organizing in a more formal way: how it’s defined, what it looks like in practice, and how to create this kind of system.

In this week’s newsletter, I’m trying something new. First, I highlight my personal work experiences with self-organizing. Then I share resources to form a good baseline understanding of this fascinating concept—it’s a bit more technical but I’ve tried to distill things for a quick(er) read.

🛤Reflecting on My Career Path

Earlier in my career, I worked for a couple of non-profit organizations with very involved boards and executive teams. I followed direction, and optimized my work efforts. Don’t get me wrong, this wasn't a bad experience, I was early in my career and appreciated the opportunity to work with others, learning along the way. In retrospect, I was given very little autonomy and this was ultimately one of the biggest challenges for me in these positions.

What would inevitably happen is I would start to grow out of my position, seeking more room to flex my intuitive and creative muscles than the job afforded. And that’s when I’d look for my next gig. I had the awareness of growing out of my job, but I didn’t know exactly why. I always thought it was because I had maxed out my skillset and needed to go somewhere new to learn new skills, to grow. This pattern of growth worked out nicely for me until it didn’t.

Before I started Meaning, I was working for IBM as a health systems researcher and consultant. I found myself working in a Department under the leadership of two people who had similar leadership styles to Gustavo: styles defined by inherent trust and de facto autonomy. I mentioned these two leaders in my last newsletter: Paul and Brian gave me the right structure and guidance to really grow into my workself, to lean into a professional confidence I had been developing over the years.

This is where life threw me a curve ball. Once again, I felt myself growing out of the job. This was a confusing time because this was the best job I’d ever had. My coworkers were great. My boss and our leadership team were great. I had the opportunity to work with state and federal government leadership on important social problems. I was being challenged, I felt I was still learning.

Things started to change slowly, people left the company, including my boss. IBM leadership began to push more on our team, we were losing autonomy. I became more aware of the hard constraints of the health system. For the first time in over a decade, I felt like maybe it was time to try something new, outside of health. Maybe there was something I could do where I could retain autonomy. A way of working where my creative instincts wouldn’t be compromised by the systems I was working within, but instead enhanced.

This is when Meaning first formed, I met Gustavo, and started to learn about self organizing work systems. I’d like to share a bit about what I’ve learned from two sources that have heavily influenced my thinking and inspired me: Frederic Laloux and his concept of teal organizations from the book “Reinventing Organizations”, and Margaret Wheatley, who is among other things, an author, consultant, and leader with a focus on new organizational forms and views organizations as living systems.

🏫Reinventing Organizations

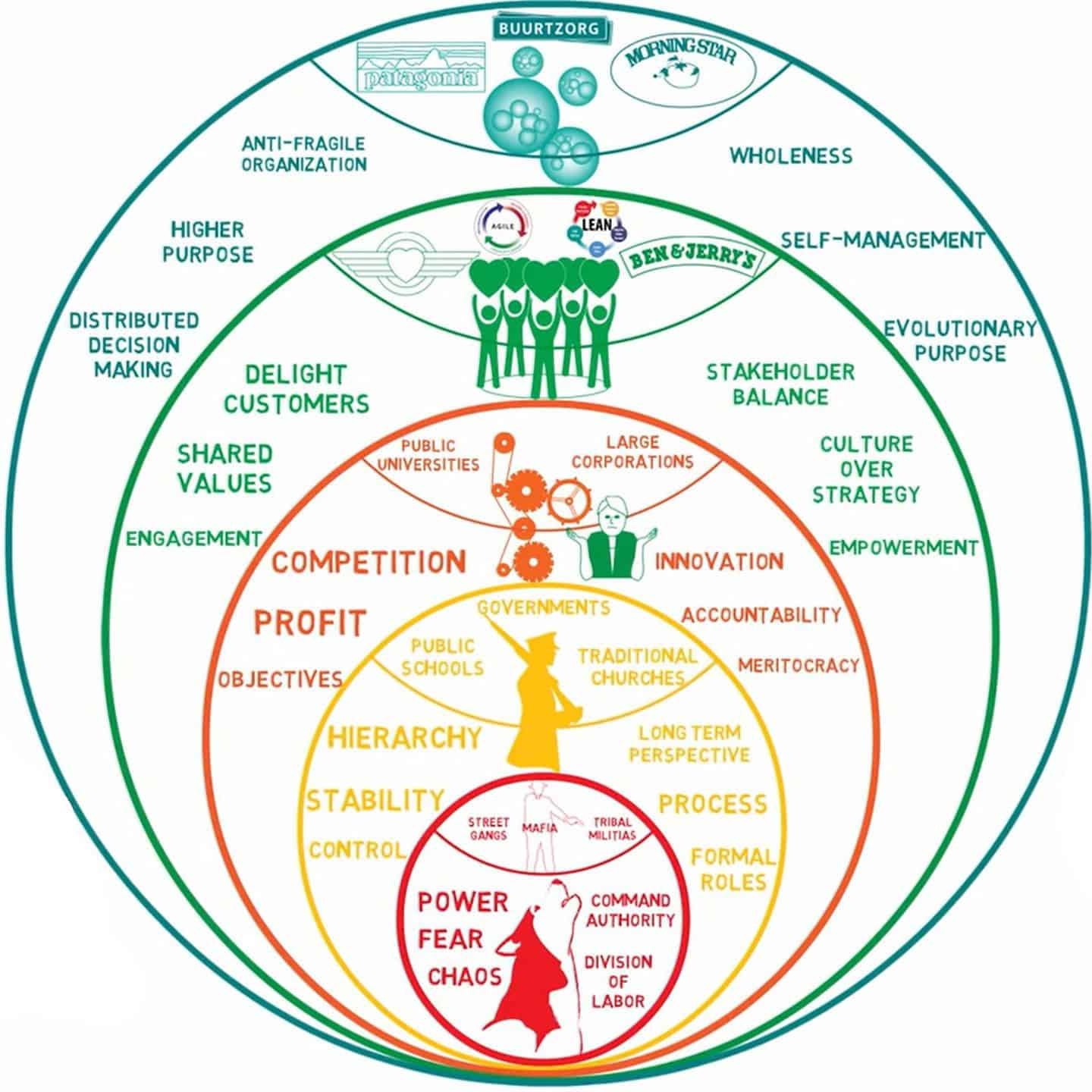

My first deep dive into self-organizing styles was through Frederic Laloux’s book “Reinventing Organizations”. One of the central themes of the book is that like biological living systems, organizational systems also evolve. Laloux walks the reader through the main models of how humans have organized, using a color to identify the major organizational models employed over time. As you’ll see, only recently have we come into self-organizing approaches (the largest circle in teal, below).

In order to understand how we got to a point in time where we’re able to discuss self-organization in human systems, I’ll provide a brief overview of Laloux’s models of human organization. These models aren’t stages in humanity in a linear sense - so it’s not that we’re leaving behind models as new ones emerge. The evolution of these organizing models is such that the emergence of new models includes what worked well from the older models, and leaves behind what didn’t work so well.

Laloux’s Organizational Models

Starting with the Impulsive-Red model, starting 10,000 years ago, the organizational style was division of labor and chain of command—with an authority figure in charge. This authority figure uses power and authority to lead. The red style does well in responding quickly and mobilizing but with so much emphasis on a singular leader, planning for the long-term is more challenging.

The next model is Conformist-Amber, starting 4,000 years ago with the shift to an agricultural society. With agriculture, there was more stability for people and we could start planning over longer periods of time. This allowed for more scalable organizational structures like governments, religious institutions, and schools. Amber organizations are governed by clear hierarchical structures and formal rules.

The Achievement-Orange model is up next, and represents our modern evaluation and incentive systems. This stage is very focused on achievement and success. Our capitalist institutions are mostly designed with an achievement-orange tilt, allowing for growth. These systems tend to operate like machines, with resources and people being optimized for roles, with a focus on producing gains. In the United States, we’ve certainly proven that we know how to work the achievement-orange model in the financial industry—successful examples of systems that are designed to enable financial growth include the stock market, investment banks, and venture capital firms.

From here we move into the Plurastic-Green model, offering a counter-balance to the machine-like Achievement-Orange by promoting relationships and values. The values most upheld in the green model are that of democracy, multiple viewpoints, and equality. The Plurastic-Green model represents a major breakaway from traditional hierarchical structures that have been prevalent in human history since the Impulsive-Red model. But the Green model is not the most practical or outcome-driven, as finding consensus across large groups without any hierarchy at all can be challenging.

Most recently, we’ve started to see the emergence of the Evolutionary-Teal model that aligns with the self-organizing systems I wrote about in the beginning of this newsletter. In the book, Laloux cites 3 main principles of these types of organizations:

- Self-management - empowering people within organizations to manage themselves, instead of traditional hierarchies or consensus-based organizations

- Wholeness - encouraging people to be their genuine selves at work, not asking for any kind of professional mask or identity to be used

- Evolutionary purpose - viewing organizations as living systems that will evolve as a result of the alignment of purpose for people within the organization

If you’re interested in these models of human organization, I highly recommend reading “Reinventing Organizations”. I haven’t even scratched the surface of all of the technologies and cultural influences that drive the transition from one model to the next.

The remainder of the book goes into detail about the Evolutionary-Teal model, with examples across the world of teal companies of all sizes and product-types. From factory workers, to in-home and community-based nursing teams—self-organizing teal organizations have been popping up more and more frequently and offer a promising new way to run a business.

I won’t describe further details about teal organizations—my intention here is to illustrate how we’ve come to a point in time where self-organizing systems are arising in the first place. For me, this opened my worldview, and research scope, into an entire world of discovery and exploration. I’ve just started this journey and will leave you with a few resources from Margaret Wheatley, an expert on self-organizing systems.

📚Margaret Wheatley

I don’t recall how I came across Margaret Wheatley’s writing but I’m a fan of how she explains self-organizing systems. Her writing is not new, some of it dating back to the 90s, but it feels exciting and new to me, and relevant to the contemporary discussion on organizations as living systems. I’ll close this newsletter by sharing some of her articles, with my most salient takeaways.

“The Irresistible Future of Organizing.” This is a great piece by Wheatley and Myron Kellner-Rogers that describes the desire for a new kind of organization. My favorite parts are:

- Organizations have an identity. This is a very interesting point to me and one I take seriously for Meaning—I anticipate that over time, as we grow, the organization’s identity will become more obvious. Identity is viewed as a lens through which the organization can make sense of the world—so it serves as guidance as an organization changes over time. Concretely, an organization’s identity can be found in its mission, vision and principles (coming soon for Meaning!).

- Living organizations operate on “the edge of chaos” - a dynamic state between stability and chaos. If you stick to a stable existence, there’s too much order and not enough room to grow; if you land in chaos, there’s not enough order and information cannot be easily understood. The happy place is on the edge of chaos. What this looks and feels like in practice? Not sure, stay tuned!

- Information should be shared freely—it’s too difficult to predict who needs what information, and when. This allows for a diversity of people to access information, and their unique perspectives on this information may be useful to the organization.

- People need to be free to interact and “run into” each other. This facilitates connection formation, which leads to networks (more on this below). Forming connections is useful because together people can come up with solutions and ideas they may not have on their own.

“Using Emergence to Take Social Innovation to Scale.” In this article, Wheatley and Deborah Frieze write about the importance of networks in self-organizing systems. Highlights include:

- Within systems, many small connections among people can give rise to larger networks. Networks offer opportunities to find likeminded people who have shared meaning and purpose in life.

- Over time these networks can strengthen into communities, where new practices are discovered. In communities people are committed not only to themselves but also to others (interdependence).

- Networks are the only form of organization used by living systems, governed by self-organization and interdependence.

- The concept of emergence is possible through self-organizing and interdependent communities. Communities have the potential for greater power and influence than the people participating in the system acting as individuals. (This aligns with Aristotle’s “the whole is greater than the sum of its parts”.)

“It’s An Interconnected World.” Wheatley explores systems thinking to explain how people are interconnected in a web-like manner. Key takeaways:

- In complex systems, such as organizations, a simple cause and effect approach to understanding how things operate doesn’t work. Interconnectivity means that there are a lot of confounding factors - it’s not as simple as explaining if X then Y, it’s more like if X, P, D, and sometimes Q, then Y.

- Even when you think you understand how things work in a system: always expect unintended consequences. I’m a big fan of this takeaway because I learned it early on in my health policy work. In systems, one of the best ways of understanding how the system operates is through unintended consequences—they are a great source of information for what is actually happening in the system.

- One of the best ways to find connections in a system is to lean into the interconnectedness by doing something, starting something, making something—and sharing it. Simply to see who notices, who comes out of the woodwork to connect with you about what you’ve created.

- Reflect on your experiences, often. And seek out understanding other people’s experiences. Understanding your perception for how a system works may be different than someone else’s perceptions. Systems are constantly changing, so checking in on your experience, and others’ experiences, is a good habit.